What makes us tick when we shop?

Customer-centric thinking and action has always been the most important premise for industry and commerce for further development and thus securing the future. But who are our customers and what are their (latent) needs? What is possible at any time in the online world, namely the tracking of click behavior along the entire customer journey, is hardly possible in stationary shopping, and only with greater investment and scope for interpretation.

The stationary store as a black box? Are we failing because of hybrid shoppers who are elusive, and do we have to resort to undifferentiated target groups (such as convenience shoppers)? No. In order to better understand our customers, it is worth taking a step back. It is not the isolated purchase of a single product or a single type of shopping cart that characterizes shoppers, but the entire process beginning with the first thought when the need arises - the "reason to buy," so to speak.

Opportunities for profiling along the shopper journey

That's why in this study we looked not only at the result (the shopping cart), but also at the origin and journey of a purchase. Not from the product perspective (customer journey), but from the customer perspective (shopper journey). A shopper journey also opens up many opportunities for profiling - not just at the shelf, but already in the living room. And: not with a watering can, but with the knowledge of an aunt Emma.

We have listened to people in numerous in-home interviews, accompanied them on their shopping trips and finally sharpened our images of the shopper journey via a representative quantitative survey. This provides us with a sound data basis (see Fig. 1).

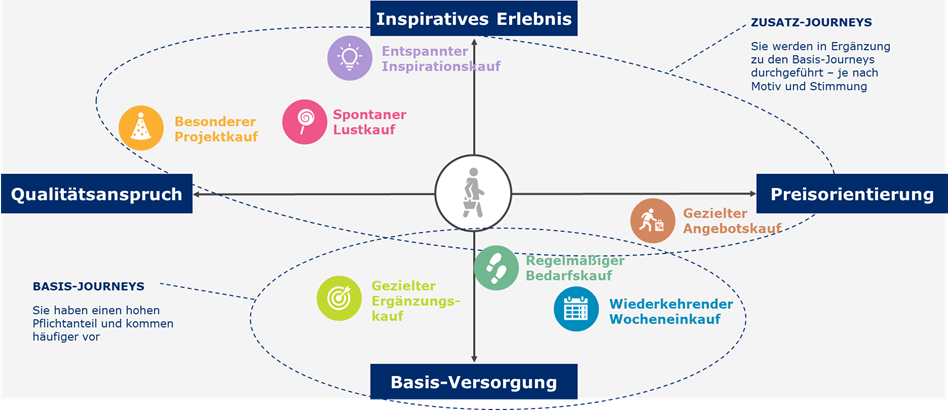

We were able to identify a total of seven characteristic shopper journeys, which we describe in detail in the study on the basis of a touchpoint analysis (see Fig. 2). The individual journeys can and should be addressed in a very targeted manner (not only in stationary retail).

It is interesting to note that many customers begin their buying process days or even weeks before they actually go shopping. In the case of recurring weekly purchases and special project purchases in particular, an intensive planning and preparation phase takes place. This opens up a time window during which customers can be played with and won over.

Great online potential for the basic shopper journey

If we look at the shopping carts and the frequency of the individual journeys, they can be divided into basic and additional journeys (see Fig. 3). Basic journeys have a high proportion of compulsory fulfillment or routinization and a high frequency - interestingly, targeted supplementary purchases are also part of this (42% state that they make a corresponding supplementary purchase 1-2 times a week; for weekly purchases, the figure is 54%, and for purchases on demand, 34%).

Not surprisingly, the online potential for basic journeys is the highest in relative terms. Here, a relief beckons. Conversely, this also means for stationary retail: creative solutions must be considered to make the basic journeys more attractive again. Compulsory purchases are usually associated with few positive emotions and thus quickly become replaceable if no added value is added to them. In contrast, additional journeys are made much more often in the stationary environment. The multisensory experience is in the foreground here. From the atmosphere, to the advice, to trying things out on site.

Not surprisingly, one and the same person regularly follows different shopper journeys. Depending on the order, the emotional situation, or even the perceived necessity. Understanding the individual shopper journeys and the optimal design of the touchpoints are an important basis for customer-centric thinking and action.

Spontaneous pleasure buying in the Shopper Journey

For example, customer experience means something completely different for a person pursuing a spontaneous pleasure purchase than it does for recurring weekly shoppers. In current experience discourses, shopper journeys are often not considered in a differentiated way. The consequence of this may be that complementary shoppers are offered inspirational impulses that can be a hindrance to their journey. It also makes sense not to want to guide the complementary shoppers through the entire store just to generate an impulse purchase. The potential for annoyance outweighs the additional purchase. Moreover, they will consciously or unconsciously store this pain point and, in the worst case, consider their recurring weekly shopping elsewhere. This would mean that much more would be lost than gained.

The challenge is therefore to pick up the shoppers in their respective shopping act and the associated mood and to meet their needs and expectations as best as possible. To do this, it is essential to know the touchpoints in order to be able to play them in a targeted manner. By touchpoints, we mean not only the media contact points (including social media), but all points of contact between customers and retailers along all shopping phases - including, for example, the parking situation, the product range, and even the use of products at home. We have identified a total of 38 touchpoints and shown their relevance for the individual journeys.

Relevant touchpoints in the shopper journey

This creates different pearl chains - i.e., different sequences of touchpoints - per journey, which must be taken into account when addressing the respective customers. What counts for them is not the individual movement with the retailer or manufacturer, but the overall impression along the journey. It is therefore important to know the relevant touchpoints and to address them in an attractive and consistent language or with a profiled service mix. And: The purchase is not completed at the checkout. The after-effect often extends to the consumption situation - e.g. when the products are celebrated in a quiet minute with a lot of enjoyment. Or in the suboptimal case, when the packaging is difficult to open.

With this study, we are laying a foundation for brick-and-mortar retailers and the industry to better understand their customers and to find starting points for more targeted profiling. Added value is created both for shopper marketing (targeted addressing of touchpoints), the total store department (design of the store layout), and for category management (different relevance of the category per journey).